Starting Again Summer 2024

Maritime History Walking Tour

click here to go to booking site

- 1 1/2 hour

- downtown

- Sitka’s maritime history from the 1700s

- local guide

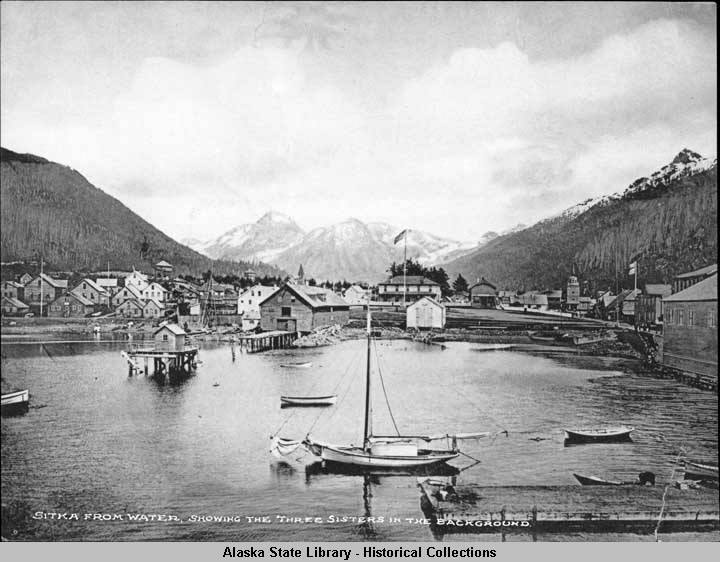

- historic images to compare with now

- $40 adults, $30 teens

Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays

1 pm to 2:30 pm

- downtown

- Sitka’s maritime history from the 1700s

- local guide

- historic images to compare with now

- $40 adults, $30 teens

Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays

1 pm to 2:30 pm

"I have lived in Alaska for 45 years and in Sitka for 12. I thought I had a good grasp on the history of the area but in just 1 1/2 hours I learned so much more about the history of Sitka and Alaska. If you enjoy history or just want to learn more about this amazing place I highly recommend taking this tour."

- Review on our booking site, 5/31/2023

- Review on our booking site, 5/31/2023

Click Here for PDF of Walking Tour Map to Print

(prints on legal size paper)

The Sitka Maritime Heritage Society is offering a summer maritime history walking tour. Below is background history for the tour. Please give it a read, give us your comments! What should we highlight? Do you have some irresistibly cool stories? Let us know!

Check Out Our Maritime History Links

Read: Sitka's First Ten Years Under American Rule

Notes for Sitka Maritime History Walking Tour

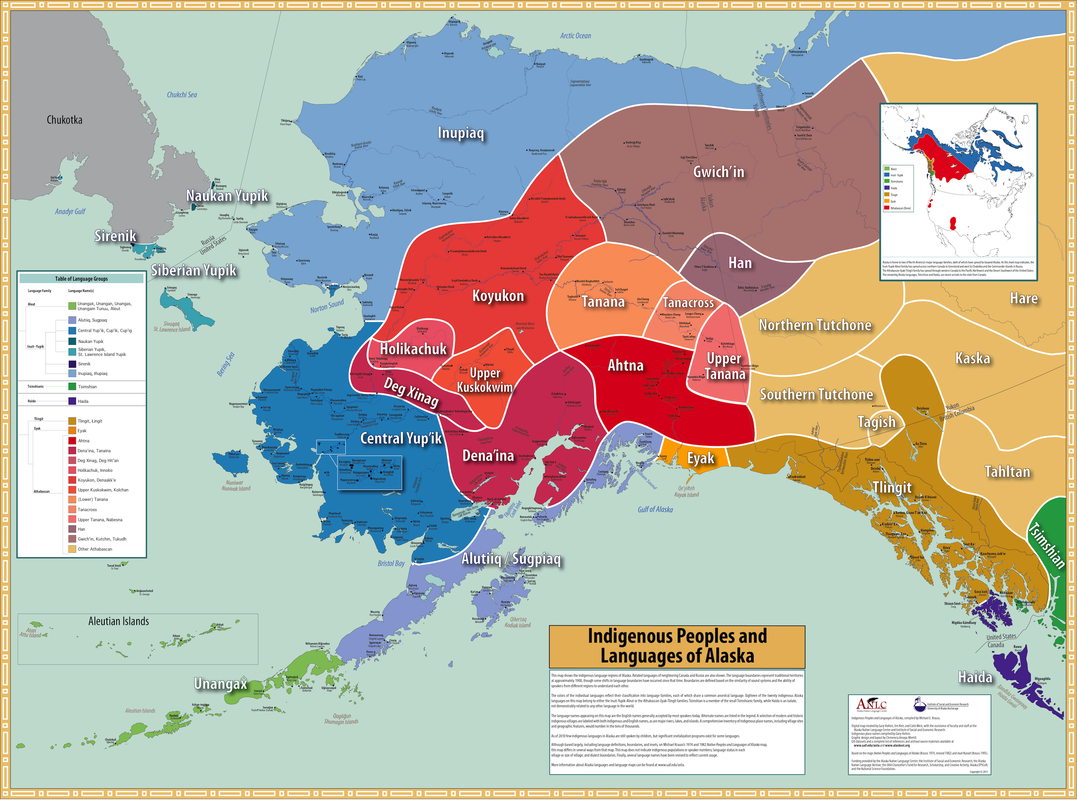

Indigenous

- We are grateful to live and work on Lingit Aani – the ancestral homeland of the Tlingit people.

- This includes all of southeast Alaska and part of Yukon Territory. The population in 1805 was similar to now, around 55,000 (73,000 now).

- As writer Ernestine Hayes has said, in a lecture in 2017: “we must always remember that before colonial contact, Native cultures possessed vigorous legal systems, effective educational systems, efficient health systems, elaborate social orders, elegant philosophical and intellectual insights, sophisticated kinship systems, complex languages, profitable trade systems—every social institution needed for a culture to flourish for thousands of years.” Systems the equal of or surpassing those of Europe.

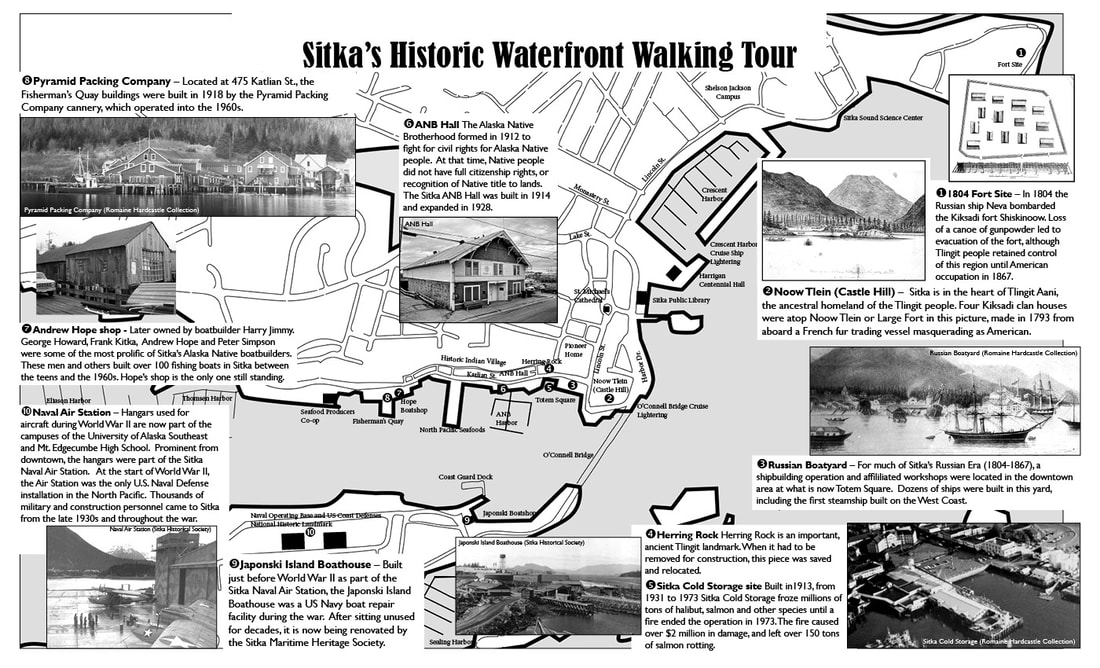

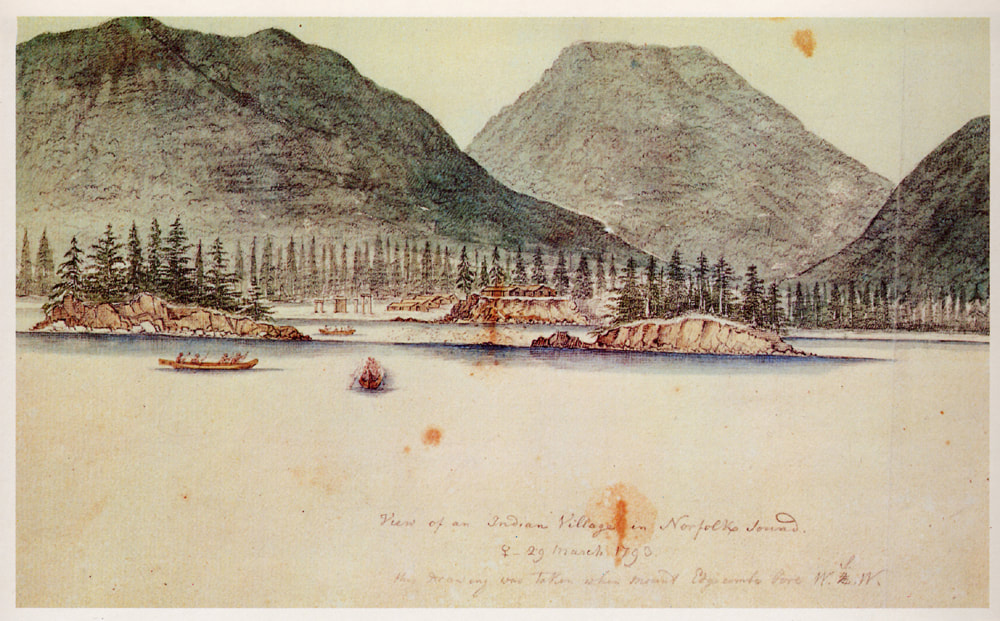

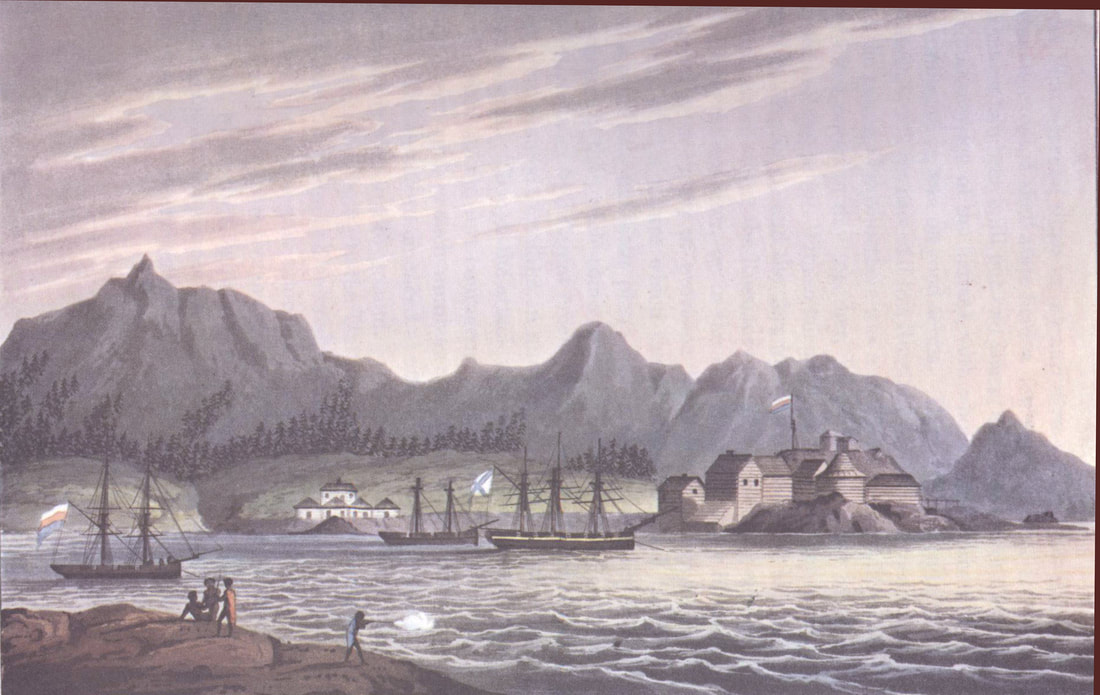

- Picture number 1 is of Noow Tlein, or “Great Fort” later known as Castle Hill, in 1793. This was a Kiks.ádi settlement – in those days towns were one clan mainly. Each clan marries into clans of the opposite moiety, so spouses and children were other clans.

- Note the large canoes in the image: at this time they were the "head canoe" type; soon after, they were replaced by the modern type, with the upswept bow. Lingit culture is a maritime culture, and people took voyages of hundreds of miles.

- The original shoreline is now buried under fill.

The Maritime Fur Trade

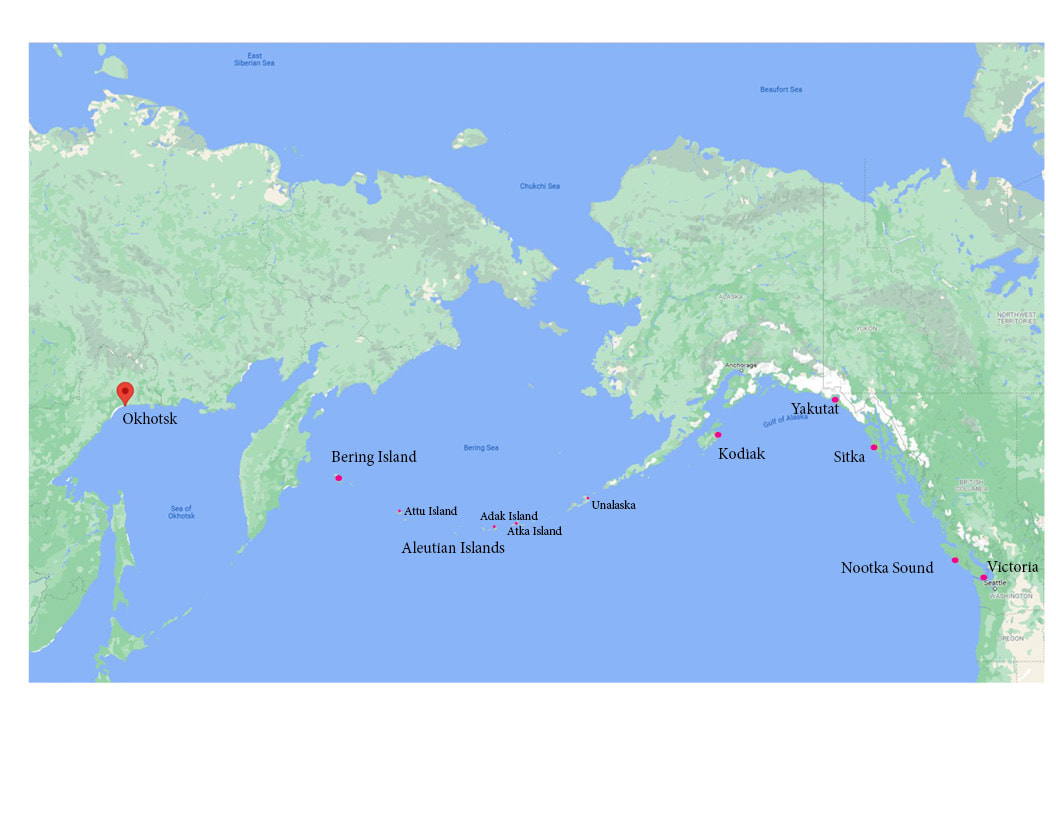

- By the 1790s Sitka was an important port in the NW Coast Maritime Fur Trade.

- The Maritime Fur Trade began on Vancouver Island in the mid 1780s. Maritime traders from various nations bought luxurious sea otter furs from Indigenous leaders for goods like guns, fabric, iron. The maritime traders then sold these furs in China, where they were prized by the nobility, for porcelain, tea and other goods, that they then carried back to sell on the domestic market.

- By the 1790s the trade was dominated by Boston ships. Americans alone sold an average of 14,000 sea otter pelts/year at Canton 1805-1812. The trade very important to the young United States, after the post-Revolution British embargo.

- Like any gold rush, it was soon over, by the 1810s. (Gibson 315)

- This picture (#1) was drawn from the deck of the Three Brothers.

- The existing NW Coast Indigenous trade, which was already extensive and lucrative, and reached from interior Alaska to California, became global. Global trade also brought smallpox and other diseases. Smallpox affects Europeans as well as Native Americans, but Native people did not have access to inoculation.

- By the end of the 1800s population of SE Alaska was a quarter or less of what it had been. These deaths caused unimaginable suffering and disruption. Nevertheless, culture thrived; masterpieces of around 1800 include the Whale House art, by the master carver Kadjisdu.áxch, now at Klukwan.

- Now we will walk to below Noow Tlein, where we will have a view of the Battle of 1804, and learn how the Russians came down here.

- Before we go, you can see the white house, built in 1916, on a Russian stone foundation for a 40-foot tall windmill built in 1819 or 1820, taken down in 1832. Later the foundation was roofed over and used for salting and storing salmon from Redoubt (a sockeye fishery the Russians depended on).

Russian fur trade

- Russians noticed the herds of sea otter in the waters off Siberia, and the rich Chinese market for them, back in the 1740s.

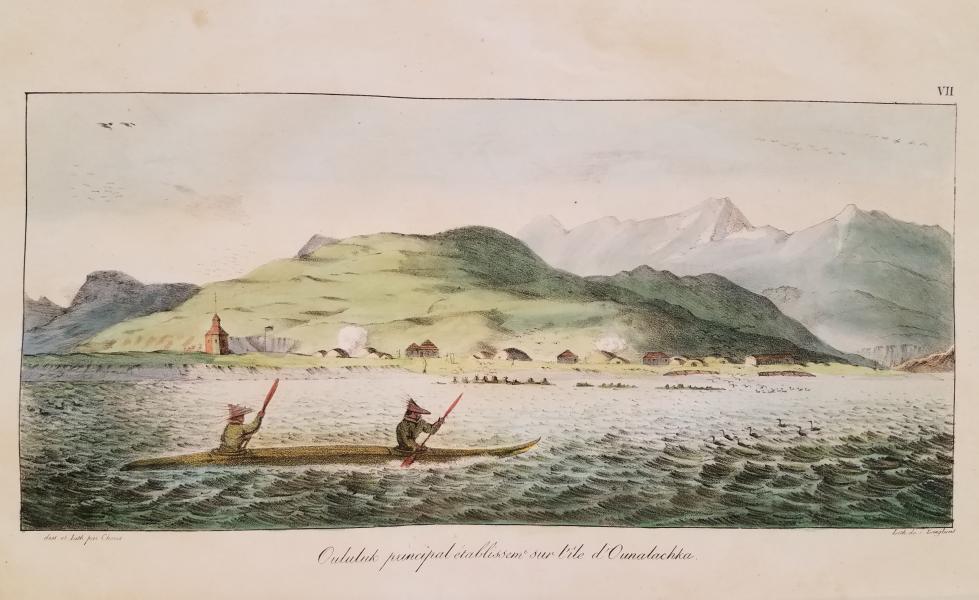

- The Unangan people of the Aleutian Islands have thriving, complex culture, hunting marine mammals from kayaks, a pinnacle of maritime technology.

- Siberian merchants financed companies to make expeditions into Alaska. Early industry brutal, violent, only interested in short term profit. As in Siberia, they would take hostages, and demand furs as tribute for the Tsar. They committed atrocities including murder and rape, Unangan people fought back, bloody battles.

- Herds soon gone nearer Siberia. By the 1780s there were only two companies left: Gregori Shelikov company conquered Kodiak; he had a vision of a New Russia, permanent colonization, in America. He brought Alexander Baranov out in 1791, age 44, as a manager.

- Shelikov forced Indigenous men to hunt sea otter for the company. They were paid but had no choice̱ they were forced laborers. Women had to sew the waterproof parkas and get food for the Russians and themselves. The Indigenous population devastated, by conquest of the Aleutians, new diseases, and by the abuses of the company in late 1700s. Population of the Aleutians dropped in 1779 to a tenth to a third of what it had been when Russians first arrived.

- Forced labor was the basis of the Russian profit in this era, just as slavery sustained the plantations of the American South.

- Built ships but frequently shipwrecked: Between 1799 and 1821 Russians built 15 ships, bought 13, sank 16.

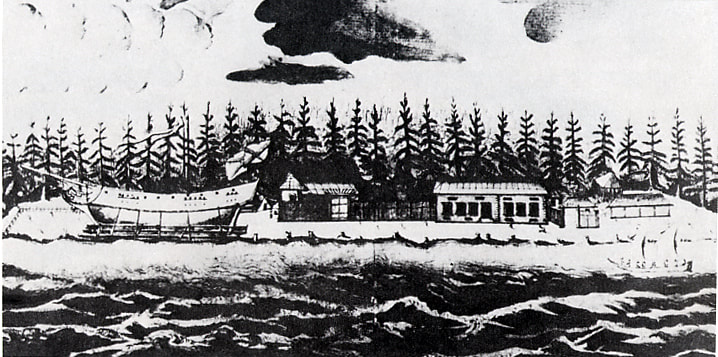

- Image is of building the Phoenix, at present town of Seward in 1794.

- In mid 1790s most of the otter gone from the Aleutians and the Gulf of Alaska. Alexander Baranov then sent fleets of hundreds of Native hunters in baidarkas (kayaks) into SE Alaska.

- 1796 he negotiated with Tlingit leader for a site for colony and a hunting base at Yakutat, (destroyed 1806) The hunting fleets took thousands of pelts around Yakutat, then in the Sitka area and as far south as present-day Craig.

- 1799 Shelikov's company became the Russian American Company,which was commercial but also authority to claim and rule colonies in North America.

- Critically, the company never had the backing of the Russian government to fully colonize North America; it was a resource extraction company, only.

- In 1799, Alexander Baranov negotiated with Kiksadi leader Shk’awulyeil for a sea otter hunting base at Gajaa Heen 7 miles north of Sitka, later called Starrigavan ("Old Harbor" in Russian) or Old Sitka.

- In 1799 115 hunters leaving Sitka died from paralytic shellfish poisoning from mussels, at a place now called Poison Cove. This and other disasters led some Kodiak Island leaders to refuse to go on the 1800 hunt: This refusal threatened the profits and thus the very existence of the Russian American Company. Baranov and his second-in-command told them they would kill those who refused to go.[1]

- Reported catch of 2,000 sea otter in 1800, 4,000 in 1801, Sitka area.

- Friction: an accumulation of insults and offenses by the Russians and their people. In the summer of 1802 a multi-clan alliance of Tlingit people led by Shk’awulyeil destroyed the fort, while another group attacked the hunters at Kuiu.

Battle of 1804 – Under Bridge

- Baranov came back 2 years later, 1804, with small boats and at Sitka met with the Russian frigate Neva.

- (Point out location of Shís’gi Noow)

- The Kiks.ádi, now led by K’alyáan, the nephew of Shk’awuyeil, built a fort Shís’gi Noow, or sapling fort, at the point at the mouth of Kaasda Héen or Indian River. The fort designed to withstand naval bombardment. It was angled and the walls were angled to deflect cannonballs, and the shallows keep ships from getting close.

- Neva towed by the hunters using their baidarkas here in front of Noow Tlein, which had been evacuated, and Russians occupied it.

- On September 29 1804 the Neva’s longboat engaged in a firefight with a canoe coming toward the fort. Here in the islands in front of Sitka, the canoe’s load of gunpowder exploded. Young Kiks.ádi leaders were lost. This was a tragedy and the turning point in the 1804 Battle.

- The Neva next moved into location on other side of Shís’gi Noow – we know because cannonballs that overshot the fort, have been found on the Sitka side of the fort's location. Alexander Baranov led an assault, disastrous, 12 Russians and Alutiiq men killed, and many wounded including Baranov.

- The Kiks.ádi and their spouses and children evacuated the fort leaving a few people and went overland to Chaatlk’noow or Pt. Craven, called the Kiks.ádi Survival March.

Russian operations at Sitka, Walking to Totem Square

- In 1805 there was a Peace Ceremony atop Noow Tlein (point it out). Only site of Sitka ceded: the Tlingit clans retained control of all their lands and of trade.

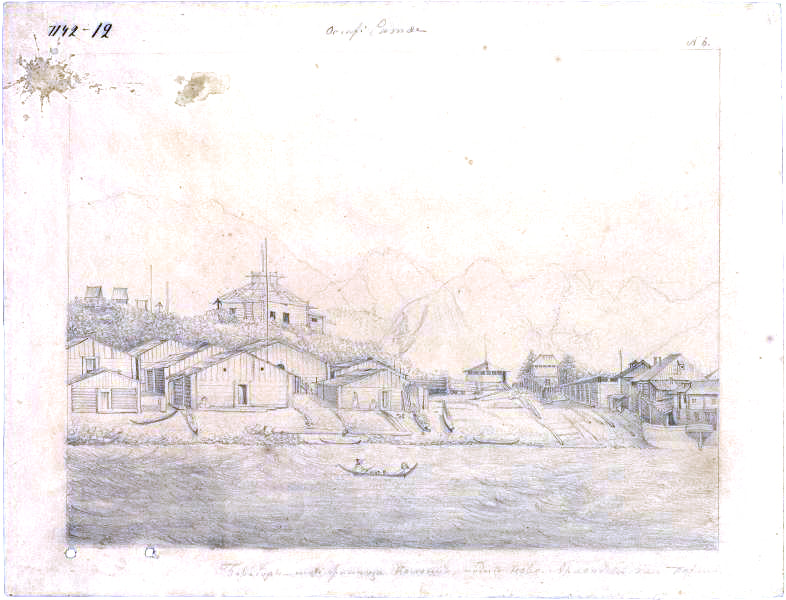

- Russian outpost at Sitka also called New Archangel after a town in northern Russia. Sitka was an outpost in Tlingit country. RAC controlled Aleutians and Gulf of Alaska, but did not control SE AK. Kept Sitka in order to claim this coast vis a vis other European countries and US.

- From 1808 to 1867 Sitka was center of operations for the Russian American Company and colonies in North America. 1812-1842 included Fort Ross in California.

- Kiks.ádi, other clans rebuilt adjacent to the Russian colony, now the Historic Indian Village, by 1828. Separated by stockade, with blockhouse where current one is. Extensive economic and social relations, sold tons of food, worked for Company, some Tlingit women married Russian men

Traces of 1800s building

- Russians had to depend on careful attention to diplomatic relationship with Tlingit to stay in SE Alaska. The Russian Orthodox Church tried to convert Tlingit leaders, but without much success; leaders objected to being excluded from worship in main church. Tlingit church site marked by a monument next to blockhouse replica.

- In the Village, over the decades, Clan houses rebuilt on sites of earlier Clan Houses in the Village. Some still standing, dating from early 20th century. Distinctive, symmetrical.

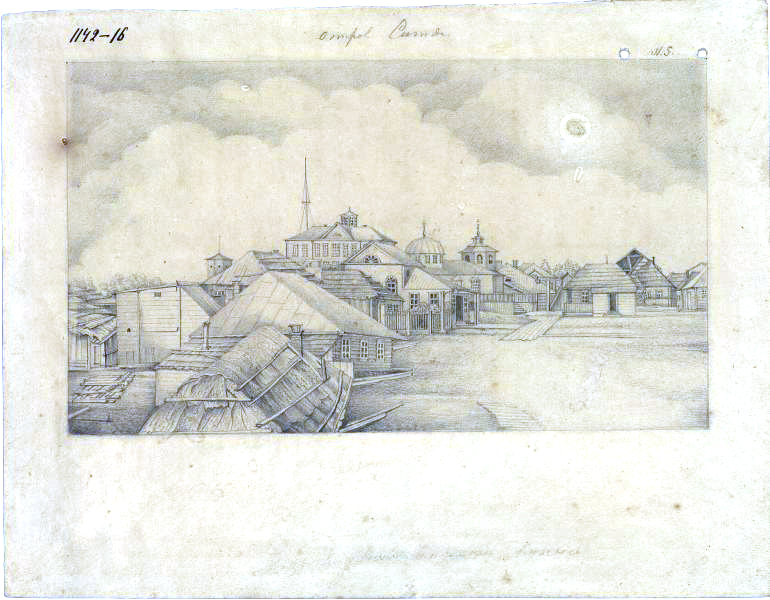

- Russian Sitka was a company town. Downtown buildings are on the sites of Russian ones: On Noow Tlein/Castle Hill, was Chief Manager’s House and offices. Below it were warehouses, a bathhouse and forge on the other side of the hill, gardens below, and a large barracks built where City Offices are now, for soldiers who came in 1850s (who were put to work)).

- The building with the dormers contains a Russian administrator’s apartments in half of it.

- The Cathedral is a replica of one built in 1848. The Russian Bishop’s House was built in 1843 when Sitka became center for Russian church in North America and Kamchatka. Several very large buildings, made of logs, beautifully crafted and built, but the Russians could never keep ahead of rot. Roofs were yellow cedar bark. Only the best had metal roofs. The Petro Marine dock was the pier, you can see the Russian-era stones, on the end, there was a warehouse.

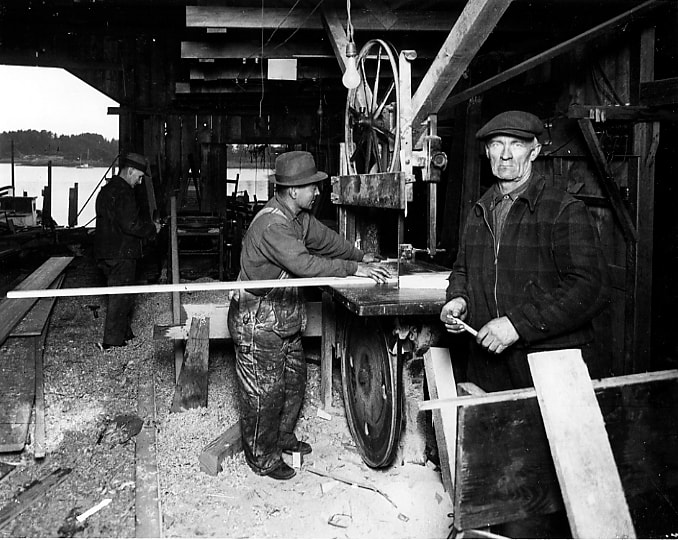

- They had a shipyard and workshops at Totem Square where we are standing. Russians built at least 24 ships at Sitka, ranging from 38 feet to over 130 feet long. But they had small workforce and a huge backlog of maintenance and building projects. They had no sawmill until 1833 and were building ships out in the open until 1834.

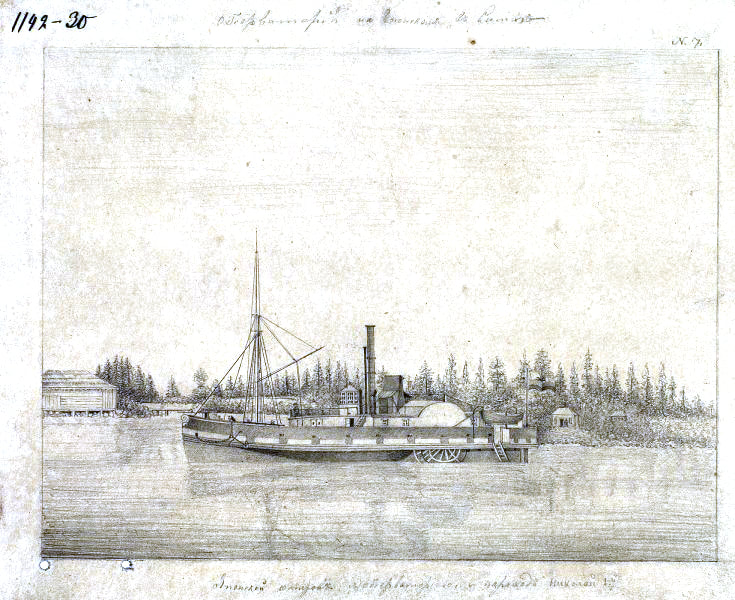

- An American engineer named Muir or Moore came out in 1838 with an American-built steam engine and built the first steam ship built on the west coast, the Nicolai. Muir built a steam engine from scratch for the vessel Mur in 1841.

- Who lived here? The Russian American Company had to pay tax on every Russian worker they brought out to work in the colonies. So, they created a new class called “Creole,” the descendants of Russian fathers and Alaska Native women. The RAC offered training and education in exchange for a period of work for the company. They also trained these people and other Indigenous people for church work.

- Alaska Native people were the main workforce of the RAC. There were only 825 ethnic Russians in Alaska at any one time, and fewer than 1000 over the entire period of colonization.

- The builder of the steamship Nicolai was an Alaska Native man, Osip Netsvetov, a member of the “Creole” class. His brother Jacob Netsvetov, later canonized as a saint, buried near the blockhouse on the hill.

Population:

- In the Tlingit part of Sitka, the population was about 1000, still with much Kiks.ádi clan representation, and now with a major Kaagwaantan presence. Each, large, house is a lineage, even as the physical houses are replaced or disappear. People of mixed ethnicity on both sides of stockade

- On the Russian side, 1860 the population of about 1000, 452 people were ethnic Russians, included 200 marines, including just 63 women or girls; 505 were “Creole” or multi-ethnic Russian and Native; and 64 were other Native people (Fedorova 205). Indigenous ethnicity in Russian Sitka was mainly Kodiak Island and the Aleutians, and some California Native from the colony at Fort Ross.

- Russian workers came out on contract, often had poor morale, because of the cold and wet and high prices and poor quality from the Company store. Managers were Navy officers, members of the Russian aristocracy, so the higher management did enjoy a library, museum, fine furnishings in the chief manager’s house.

- Economics: after sea otter hunted out, RAC did try conservation in Aleutians, but dealt in land furs, Pribilof Island fur seal pelts, tried selling timber, fish, mining, nothing worked out except ice to Gold Rush era California, but US and RAC ships – Zenobia Rock named 1855 for an American ship in ice trade that found it the hard way.

- However the Company never did find a replacement for sea otter. One source of income was the markup on supplies and clothes they sold to their own employees. Much food, and manufactured goods had to be imported. They also supported widows and retired or disabled workers, and supported churches and clergy and medical facilities and transportation. Not profitable.

- The economy of the wider region, Tlingit Aani, in the 1850s was also the global fur trade. Powerful clans owned trading rights with the interior and defended their rights against the Hudson’s Bay Company.

- By 1851, Tlingit traders bypassed the Russians at Sitka and took furs by canoe, 600 or more miles to Victoria, to trade with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Puget Sound became regional economic center for SE AK. British and Euro-American settlers pouring into the region, backed by aggressive military forces.

- The Russian occupation of SE Alaska very weak compared to US and British occupation of British Columbia and Washington. An attack on Sitka in 1855, via the Tlingit church built into the stockade, monument there now, left 5 or 6 dead Russians and dozens wounded. RAC did not retaliate as British or Americans would have done. Instead, they blamed their manager for allowing relations to deteriorate, and worked to make peace. Relied on diplomacy to stay in SE.

The Transfer, 1867 - Totem Square

- Russia gave up the Alaskan colonies because it was not profitable and could not be defended.

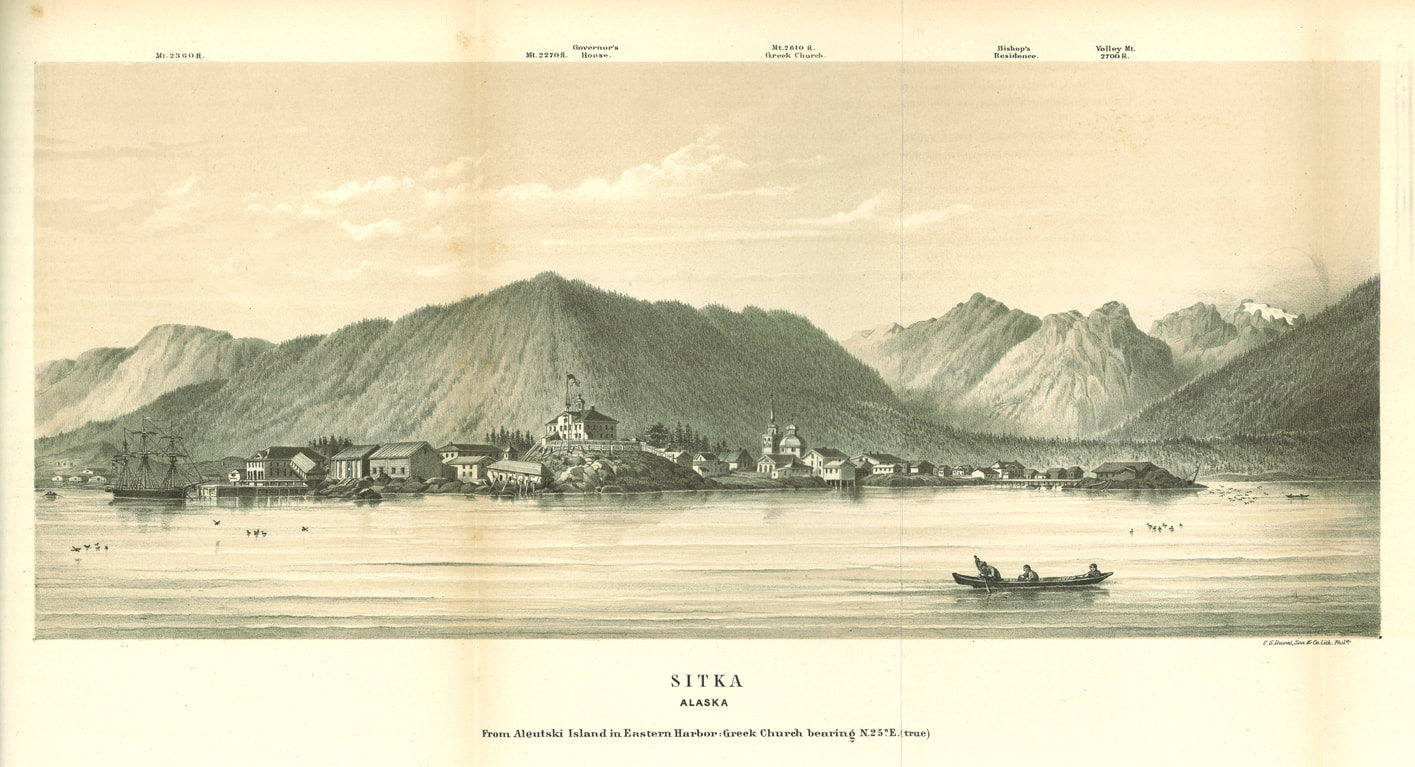

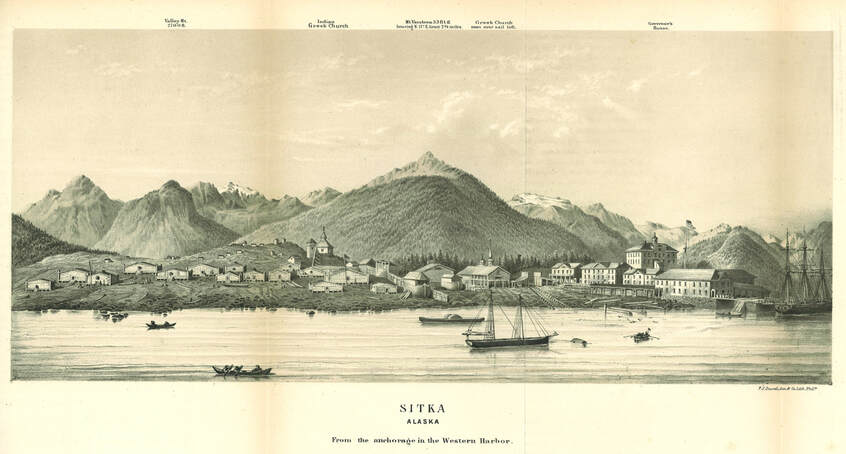

- In 1867 Russia’s claims in Alaska were transferred to the United States. Claims not defined. The ceremony took place on Noow Tlein/Castle Hill on October 18th 1867. These pictures done from aboard the USS Lincoln in 1867.

- Tlingit people, the actual owners of southeast Alaska, were not invited. They observed the ceremony from canoes from the water. Excluded from citizenship. The transfer was a catastrophic event in Tlingit history.

- Tlingit leaders protested from Day 1 that Russians had no right to any land other than townsite of Sitka. Kiks.ádi leader Kooxx'aan, house roughly where Naa Kahidi is, initially refused to lower the Russian flag in front of his house, right next to the stockade.

- (Pioneer Home: 1913 in the old marine barracks (built 1892), to house destitute men who had came to Alaska with gold rushes, etc. This building built 1934, enlarged in 1956 to include women. Still a nursing home.)

- Alaska managed by US Army for 10 years as a possession.

- The fur trade collapsed in 1870s, with world-wide Long Depression. Aggressive American traders pushed Tlingit traders out of the market that was left.

- US military much more powerful than Russians, also brought virulent racism. This was the era of the Indian Wars, ethnic cleansing of the US, often genocidal in impact. The height of Manifest Destiny.

- Army’s goal in Alaska was to put down “insolence” and demand subjugation.

- Indigenous law requires compensation by the group (classically, the clan) for any injury even if accidental. This had been the law of the land, followed by Russians and independent American traders.

- The Kake War, 1869: Army sentry killed men leaving Sitka by canoe. Relatives of two of those killed, from Kake, asked for compensation, which had been the custom. Refused. Relatives killed two Americans. USS Saginaw leveled three villages and burned all the houses but one to the ground, a total of 28 clan houses, many of them 30 or 40 feet square, and most of the canoes. A similar incident happened in 1869 at Wrangell.

- 17 years of military rule: Army here to 1877. Then Treasury Department, by the ships of the US Revenue Cutter Service, then Navy 1879-1884.

Civilian government in 1884, 1880s Economy – Herring Rock

- The Yaaw Teiyi or Herring Rock was under where the Totem Square Inn is now, this piece was saved. It is landmark linking history, the Kiks.ádi clan and this place. Ancient stories and names connect this rock to people today.

- The Sheet'ka Kwaan Naa Kahidi, or Community House, is on the site of a Bureau of Indian Affairs school for grades 1-8. Sitka's Native children were segregated from the non-Native children until integration in 1949. Native youth could not go to the Sitka High School. They had to go to the private Presbyterian boarding school Sheldon Jackson or leave town, and attend the BIA school at Wrangell or other Native schools.

- In the 1880s, canneries and tourism and mainly mining took off. Canneries took salmon streams without compensation to Native owners. Non-Native miners allowed to stake whatever they wanted Tlingit people consistently petitioned for citizenship, and the same rights that newcomers had, and compensation for resources and lands taken. Authorities denied, saying not owed compensation, under the Doctrine of Discovery, in which Christian nations had the right to take over non-Christian lands and peoples, and that they were “uncivilized” and so not ready to be citizens.

- One consequence: Tlingit clans had owned and strictly regulated salmon fisheries; unregulated exploitation led to permanent damage. Similar later for herring stocks..

Christianity, the ANB – ANB Hall/Parking Lot

- The Christian Native village of Metlakatla, 1861, in Canada was famous all over the coast. Over a thousand Tsimshian people built their own Christian community with their own sawmill, cannery, church, and new homes. This was probably in response to the government and settlers seizing Native lands and resources.

- Tlingit leaders asked for missions, likely part of the ongoing effort for rights and opportunities. The Presbyterian mission built its first building in 1882 now site is the Sheldon Jackson School NHL. Prominent Sitka clans sent their sons. But soon fell out of popularity, over the 5-year indentures parents had to sign, and intention to create workers, not business owners.

- There was intense competition between the Presbyterians and the Russian Orthodox church in the later 1880s. Both wanted to replace Tlingit spiritual practices, culture and political power, but -- both had to hold back in order to be competitive.

- 1904 was the “Last Potlatch” by permission of Presbyterian Governor John Brady, hosted by Kaagwaantaan clan Wolf houses in center of Village. A demonstration of wealth, culture art and power.

Both ROC and Presbyterians had organizations, meetings and schools in the Village. - Alaska Native Brotherhood, 1912, first Native American civil rights organization. Crystalized decades of effort for recognition of ownership of resources and lands, and, fight for citizenship and civil rights. The hall built in 1914, enlarged in 1928. Native people not citizens until 1924.

- Social and economic capital for the ANB came out of the commercial fishing and boat building industries.

Commercial Fishing – ANB Harbor

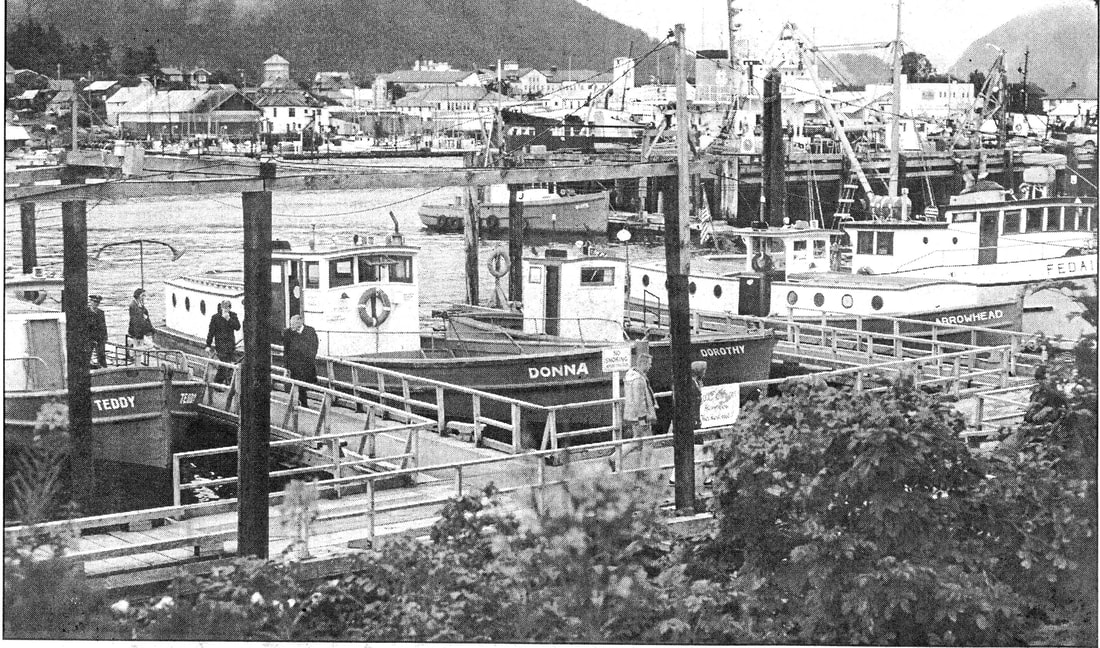

- 1900s: small internal combustion engines made it possible for independent fishermen; refrigeration sparked the troll fishery (hook and line for salmon, shipped East for smoking), and turbo charged the halibut fishery. Fishing dominated Sitka economy. (Point out vintage fishing boats)

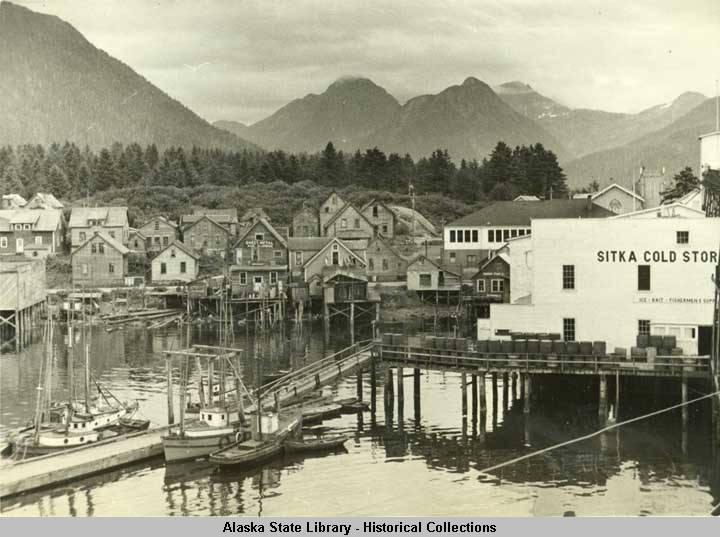

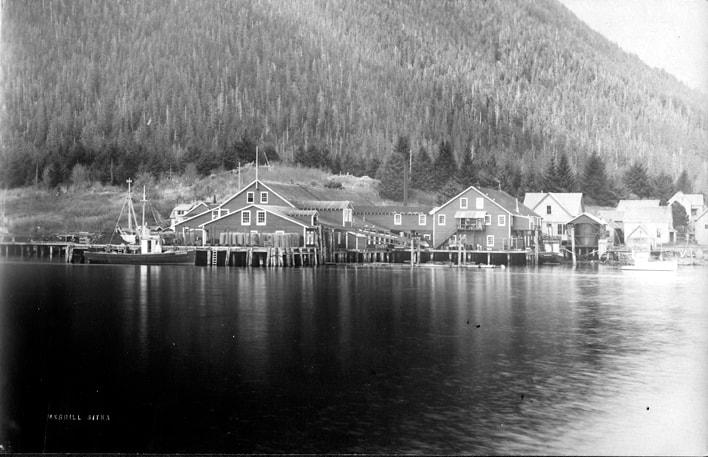

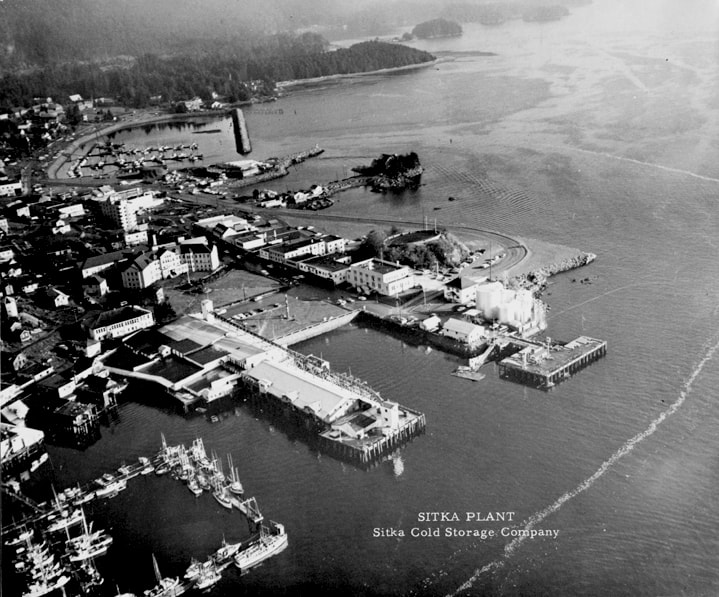

- Cold Storage built 1912 burned in 1973. Indicate site of Cold Storage

- Commercial seining (catching salmon with a net), for canneries, was dominated by AK Native men into the 1970s.

- Many Sitka Native families shared a tradition of going to cannery, mainly north of here – a family could seasonally live and work at the cannery, while men commercial seined - also get fish other foods for themselves, berries, and planted potatoes at their clan-owned garden sites on the way out, and harvest in the fall on the trip home.

- Pyramid Packing Company built 1918, post WWI boom. The building still there, now Fisherman's Quay and LFS marine supply store, near other end of the Village.

- Boatbuilding dominated by AK Native boatbuilders. Boat styles were probably introduced by Norwegian immigrants. Boat shops here on Front Street, on other side of ANB Hall, two others farther on, one still there, next to LFS (Pyramid).

More Fishing – Begin Walking Back to Totem Square

- Peter Simpson Tsimshian, came to Alaska with exodus of people from Metlakatla, Canada to New Metlakatla, Alaska, in 1887. Father of Land Claims, Founder of ANB; built boats at the Cottages, a Christian Native settlement on mission grounds, at the entrance to Sitka National Historical Park.

- Longlining for halibut was also a Native fishery but became mostly Norwegian out of Seattle.

Many immigrants, mainly Scandinavian, who became trollers and longliners, and Chinese and Japanese and later Filipino immigrants, worked in and managed canneries and took part in and owned other businesses, especially restaurant industry. - Racism was still pervasive in 20th century. No citizenship for Native people until 1924 except by individual petition, and no recognition of original land ownership. School segregation until 1949. Naa Kahidi is on site of BIA school, donated by Kiks.ádi leader K’alyaan. Native kids had to go there until 1949, then integrated. No local high school option for Native youth - not allowed to attend Sitka High School - except the private Sheldon Jackson School. Had to go to Wrangell Bureau of Indian Affairs School or elsewhere.

- High rate of death of young people, especially tuberculosis, a consequence of racial discrimination. The consequences of racist discrimination against a group perpetuates the myth that it is due to something inherent to that group, when is it really the result of the bias itself. We need to see each other and treat others without stereotypes, as individuals. We can all benefit by learning more about Tlingit culture technology and language.

WWII -- Totem Square

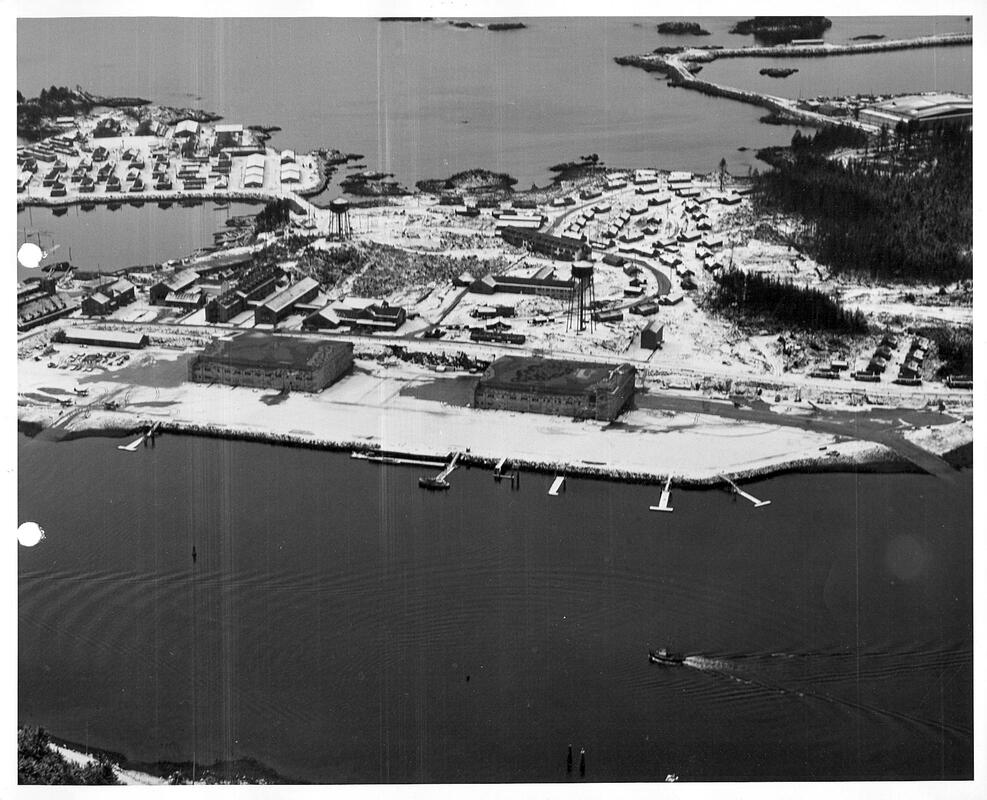

- In 1930s Sitka chosen as a site for a strategic defense base for North Pacific, against the threat posed by Japan. The only defenses for the North Pacific during the war were here, Kodiak and Dutch Harbor. In 1937 first Navy seaplanes based here, 1939 began building Naval Operating Base for PBY long-range reconnaissance seaplanes.

- The islands were blasted, connected for the Army Coastal Defenses constructed to defend the air station. The plan was to have 3 batteries of 6-inch guns covering Sitka Sound against enemy vessels. Each with 2 base end stations for aiming the guns, with searchlights and communications cable.

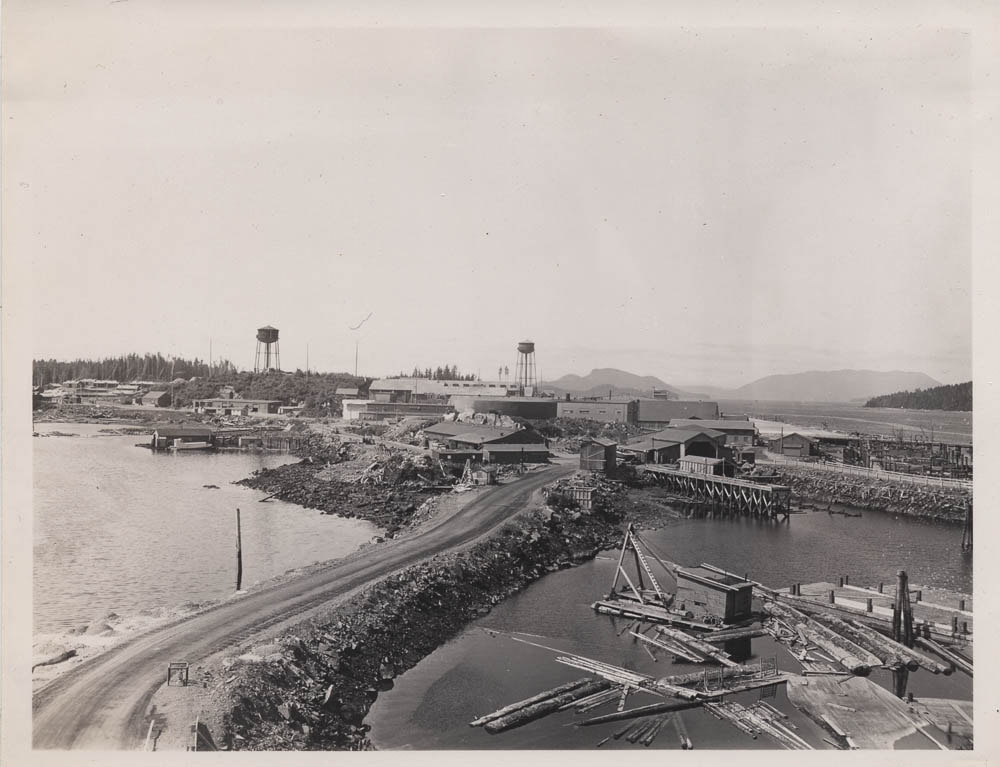

Big influx of thousands of contractors and military in 1939, jobs and dollars, as well as alcohol and violent crime. Sitka mainly important as a waypoint for PBY amphibious planes on way to Aleutians, after Japan attacked and occupied Attu and Kiska Islands. - What you see are two hangars for maintaining the PBYs, an apron the size of a carrier deck with tie downs, and ramps for bringing the planes onto land. Above are the Navy Communications, Recreation, Mess hall and Barracks. The Army base was beyond on Alice and Charcoal Islands, and eventually on a 1 ½ mile Causeway connecting to the battery at Makhnati Island.

- The Navy’s boat repair shop and haul out built 1941, the Japonski Island Boathouse marine ways. Had a big fleet of boats here, for Army and Navy, had to be repaired at the tiny marine ways, probably intended as winter storage and for light maintenance, but they built a shop and storage wings and made do. They also had a tidal grid and a floating marine ways, but it was inadequate for the over 40 shipwrights employed by the Navy.

Commercial Fishing, Economy Since WWII – continue Totem Square or (long version) go Over Bridge

- After the war, thanks to lobbying by the ANB, Navy facilities repurposed as the Mt. Edgecumbe BIA school for Alaska Natives, now run by state of Alaska, and tb sanitarium for Natives, now Mt. Edgecumbe Hospital. This hospital and one in Anchorage could take only a small fraction of the people sick with tb in the devastating epidemic. Drugs were developed in the 1950s. Nearly every Native family lost children or a parent. Peter Simpson, the boatbuilder and civil rights leader, and his wife had 15 children; only two survived to adulthood and both died early, leaving children. This story was repeated all over Alaska; you can imagine the impact.

- The federal facilities on Japonski Island was its own town, even had its own post office, called Mt. Edgecumbe. People came back and forth on the Shore Boats, a Navy term, that ran on the half hour. The boat shop was used for repairing the Shore Boats, by master boatbuilder Bob Modrell. Point out location of two docks.

Commercial Fishing, Economy Since WWII – continue Totem Square or (long version) go Over Bridge

- Bridge built in 1972.

- Statehood, milestone finally achieved in 1959; fish traps were a big issue. Under federal management, the big companies were cozy with federal regulators and could do what they wanted. Advent of fish traps, they employed fewer Alaskan fishermen, and could easily overexploit fish streams. The ANB took a leading role in fighting for statehood so the state could manage its own resources. One of the first acts of the new state was to outlaw fish traps.

- Next milestone: longline boom of 1980s: Magnuson Act 1976 claimed control of ocean fisheries to 200 miles from shore, which included the sablefish or black cod fishery, with a strong market in Japan. Halibut had been rebuilt, and opened again at about the same time, leading to the 1980s longline “gold rush,” with great profits, but also loss of boats and lives. This was reformed in the IFQ system, where fishermen were given and then can buy and sell a portion of the total catch of the resource. Longline fisheries landings still a major part of fisheries value. Point out modern longliners, Sitka Sound Seafoods, HPC, tell Silver Bay, Sitka Salmon Shares

- Herring: this fishery for eggs and oil was highly valued and stocks grew under Tlingit management. But, a herring oil and fish meal industry nearly destroyed the fishery in the 1930s-50s. Then in the late 20th century, a herring roe fishery (for sale to Japan, which had overexploited the fishery there), in which fish are harvested and the females stripped of their eggs (roe), led to collapse of more herring stocks. Fortunately the Japanese market for herring roe is shrinking, and there was no fishery in Sitka Sound in 2019 or 2020.

- During herring spawn, the waters near shore turn milky, as the fish deposit their eggs; people set out hemlock branches for eggs, to freeze and to eat fresh.

Picture of herring eggs drying. - In 1959 pulp mill built in Sitka (7 miles south of town) which was Sitka’s main employer until it closed in 1993; Sitka was a mill town. We are in the vast, Tongass National Forest, which is contiguous with southeast Alaska – its creation in 1905 was the major taking of Tlingit lands by the U.S. government. In southeastern Alaska trees grow very slowly, unlike Oregon or Washington, here it is a century or more before forest can be cut again. Also, the big old growth trees that are valuable to the industry comprise only a small portion of the forest, and create vital habitat for salmon and other creatures. The pulp mill contracts were cancelled in the 1990s because they were unsustainable and would have done permanent damage to fish and wildlife populations.

- Point out line on Verstovia from Russians, few places around commercially logged.

- Russians never conquered or had treaty with Indigenous people of Alaska. 1867 Treaty of Cession with US left undefined what the “possessions” were. Land Claims finally settled in 1971, in order to clear the way for the Alaska Pipeline. There would have been no rights to settle without Tlingit lawyer William Paul and the ANB. The Alaska Native Land Claims Settlement Act (ANSCA) signed in 1971. Created regional Native corporations, with Native people as the shareholders. Corporations now a major political and economic force.

- When the mill closed, fear that Sitka would decline, but, by then was tourism, nonprofit regional health consortium SEARHC, UAS, USCG Air Station Sitka, commercial fishing – not so different from 1900 – a truly diversified economy. Sitka’s biggest population growth had been 1970-1980

- Most today see the value of the forest intact – for salmon and tourism – with limited, locally-processed timber - as worth more than its value as large-scale clear cuts for export as round logs and pulp.

Fishing now – we have notably well-managed salmon and other fisheries - eat wild fish – unlike most of the globe, is sustainably fished.

Commercial Fishing, Economy Today – continue Totem Square or (long version) Japonski Island Boat Shop

- Tourism – together with other nonprofits and businesses, we are building as arts, culture, heritage destination –

- Preserving this building, to keep feel of history, preserve and share our maritime heritage thru interviews, classes, videos, boat building skills

- SMHS – we are fixing up the building, teach classes – do tours – oral history events – and recording, programs for kids – please join us!

A Short Maritime History of Sitka, Alaska

The Tlingit Maritime Tradition

Tlingit fishermen (Sitka Historical Society collection)

The Indigenous people of Sitka, the Tlingit, have a rich and ancient maritime tradition. They used large red cedar canoes traded from the Haida to transport groups of a dozen or more people to gatherings and to seasonal camps and to trade a thousand miles up and down the coast.

Smaller spruce or cottonwood canoes were used for fishing, berry picking, seal hunting, and other daily uses. The canoes were hollowed from a single log, then steamed open into a final shape.

Smaller spruce or cottonwood canoes were used for fishing, berry picking, seal hunting, and other daily uses. The canoes were hollowed from a single log, then steamed open into a final shape.

18th Century European Explorers and Sea Otter Traders

Mt. Edgecumbe, the dormant volcano at the entrance to Sitka Sound, was given its name by Captain James Cook when he saw the volcano on a voyage around the world in 1778. Captain Cook, who most likely named the volcano after a mountain of the same name nearly Plymouth Harbor in England, was among many explorers to enter the waters of Sitka Sound during the Age of Exploration. And, he was certainly not the first.

Among early Europeans to the area, Russian navigator Aleksei Chirikov entered Sitka Sound in 1741 and named the volcano Mt. St. Lazarus. Later, in 1775, Spanish explorer Don Juan de la Bodega y Quadra named it Mount St. Hyacinth or San Jacinto, because it was that saint’s day when he spotted it.

In the 1780s traders came from Europe and the United States to buy sea otter furs for guns, tools and fabric, which Tlingit traders traded up into the interior and up and down the coast.

Among early Europeans to the area, Russian navigator Aleksei Chirikov entered Sitka Sound in 1741 and named the volcano Mt. St. Lazarus. Later, in 1775, Spanish explorer Don Juan de la Bodega y Quadra named it Mount St. Hyacinth or San Jacinto, because it was that saint’s day when he spotted it.

In the 1780s traders came from Europe and the United States to buy sea otter furs for guns, tools and fabric, which Tlingit traders traded up into the interior and up and down the coast.

The Russian Era (1790s-1867)

The Russian presence in Alaska began in the Aleutian Chain in the 1740s, when Russian traders and hunters moved east from Siberia seeking sea otter pelts. Sea otter were worth a fortune in China. The Russians forced Unangan and coastal Native people to hunt sea otter for them from two-hole baidarkas.

The Russian American Company formed in 1799 with rights to colonize America on behalf of the Tsar. The first Russian fort at Gajaa Heen (Old Sitka, 7 miles north of present day downtown Sitka) was built in 1799, and destroyed by the Tlingit in 1802.

In 1804, Russian American Company chief Alexander Baranof returned with hundreds of Chugiak, Sugpiak, and Unangan Native hunters and met the armed Russian ship Neva at Sitka. After a battle with the Tlingit Kiksadi Clan and allies at the Indian River, the Russians established their permanent settlement, New Archangel, at what is now downtown Sitka.

As the headquarters for the Russian American Company, New Archangel was the administrative center for the Russian colonies that reached all the way to California. Sea otters had been hunted nearly to extinction by the early 19th Century, but New Archangel remained the administrative center of the Russian colonies, with boat building, with a boatyard that produced dozens of ships. It was also a stop along trade routes, where European and American boat repairs could be done. The Russian boatyard was about where Totem Square is today.

Nevertheless, Russians held only the colony at Sitka, and the Tlingit held all their lands as they had before.

The Russian American Company formed in 1799 with rights to colonize America on behalf of the Tsar. The first Russian fort at Gajaa Heen (Old Sitka, 7 miles north of present day downtown Sitka) was built in 1799, and destroyed by the Tlingit in 1802.

In 1804, Russian American Company chief Alexander Baranof returned with hundreds of Chugiak, Sugpiak, and Unangan Native hunters and met the armed Russian ship Neva at Sitka. After a battle with the Tlingit Kiksadi Clan and allies at the Indian River, the Russians established their permanent settlement, New Archangel, at what is now downtown Sitka.

As the headquarters for the Russian American Company, New Archangel was the administrative center for the Russian colonies that reached all the way to California. Sea otters had been hunted nearly to extinction by the early 19th Century, but New Archangel remained the administrative center of the Russian colonies, with boat building, with a boatyard that produced dozens of ships. It was also a stop along trade routes, where European and American boat repairs could be done. The Russian boatyard was about where Totem Square is today.

Nevertheless, Russians held only the colony at Sitka, and the Tlingit held all their lands as they had before.

After the Transfer to the U.S.

Following the 1867 transfer, Alska Native people were not citizens. The U.S. Army was much stronger than the Russians had been, and asserted government dominance over the Alaska Native people. U.S. Army troops were quartered in Sitka for a decade, until 1877, then for a short time Alaska was administered by the a few Collectors of Customs and Revenue Cutters. Then, in 1879 the Navy was given jurisdiction over the District of Alaska, which resulted in Navy gunboats being based in Sitka. These government vessels were the only law in Alaska.

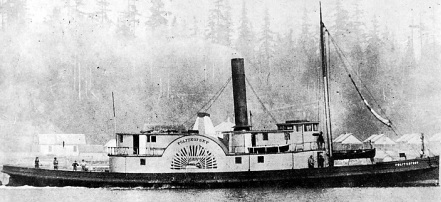

Sitka's economy was extremely depressed through its early years as an American outpost, especially the Tlingit were affected as American newcomers took over what trade there was. In the 1880s outside industry started coming in, that unfortunately took Native land and resources. As it does now, Sitka had a diversified economy, relying on tourists who came up on steamships as well as the short-lived sealing industry, among other things. When high-seas sealing was outlawed, Natives were granted an exception if they hunted in small boats, with spears. The Sitka Native boatbuilders developed the “Sitka sealer,” a 20- to 24-foot open boat.

Sitka's economy was extremely depressed through its early years as an American outpost, especially the Tlingit were affected as American newcomers took over what trade there was. In the 1880s outside industry started coming in, that unfortunately took Native land and resources. As it does now, Sitka had a diversified economy, relying on tourists who came up on steamships as well as the short-lived sealing industry, among other things. When high-seas sealing was outlawed, Natives were granted an exception if they hunted in small boats, with spears. The Sitka Native boatbuilders developed the “Sitka sealer,” a 20- to 24-foot open boat.

Boat Building in Sitka

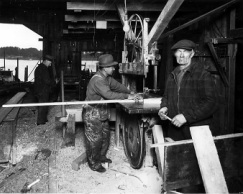

Andrew Hope in his shop (Sitka Historical Society)

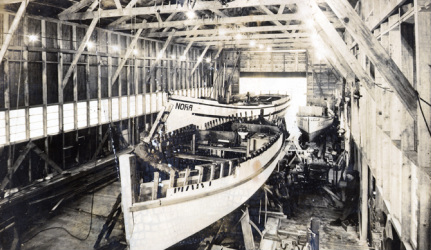

The most prolific period of boat building in Sitka occurred at the turn of the 20th Century. From 1900 to 1960 over 100 documented vessels of at least 32 feet were built in Sitka. Many salmon and longlining boats still in use today were built during this era. These boats are extremely seaworthy with deep, heavy, relatively narrow hulls.

At its peak, Sitka had eight boat shops. Peter Simpson, a graduate of Sheldon Jackson, had a boat shop at the cottages near Sitka National Historical Park as early as 1907. Other shops were on islands and Katlian Street. Most boat builders were Native men, but some were European immigrants. Aside from Simpson, highly productive boat builders of the era included Andrew Hope, Peter Kitka, and George and David Howard.

Additionally, many fishermen built their own boats, and the Sheldon Jackson school built two boats: the SJS and the Princeton Hall. After World War II, shipwright Bob Modrell taught boat building at the Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school, where his students built a troller and a deckhouse for the shore boat Arrowhead.

Also, shortly after the War, the Sitka Marine Railways opened at what is now Allen Marine. Six boats were built there in 1945 and 1946 alone, but the main focus of the operation was on boat repair.

At its peak, Sitka had eight boat shops. Peter Simpson, a graduate of Sheldon Jackson, had a boat shop at the cottages near Sitka National Historical Park as early as 1907. Other shops were on islands and Katlian Street. Most boat builders were Native men, but some were European immigrants. Aside from Simpson, highly productive boat builders of the era included Andrew Hope, Peter Kitka, and George and David Howard.

Additionally, many fishermen built their own boats, and the Sheldon Jackson school built two boats: the SJS and the Princeton Hall. After World War II, shipwright Bob Modrell taught boat building at the Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school, where his students built a troller and a deckhouse for the shore boat Arrowhead.

Also, shortly after the War, the Sitka Marine Railways opened at what is now Allen Marine. Six boats were built there in 1945 and 1946 alone, but the main focus of the operation was on boat repair.

Sitka as a Fishing Port

The Myrth, a troller built in Sitka

As long as there have been people in the area that is now Sitka, people have depended on the rich salmon and halibut stocks. Sitka didn't become a large-scale commercial fishing port, though, until after the transfer to the United States.

SALMON

The first Salmon cannery in Alaska opened in Klawock on Prince of Wales Island in 1878. That same year one was built at Old Sitka, but it soon closed. Seining and later traps supplied the fish for canning.

Sitka didn't have another fish plant until 1913 when Booth Fisheries cold storage opened. It became Sitka Cold Storage in 1930. Today the old Sheffield Hotel stands on the site. Pyramid Packing cannery opened a few years later in 1918. It is still standing as the Murray Pacific building. Canneries in Peril Strait and at Sitkoh Bay (Chatham Cannery) also employed Sitkans.

The struggle for Native citizenship and land claims began when people had their traditional fishing stream rights taken by canneries. Prominent leaders and the founders of the Alaska Native Brotherhood, which fought for Native rights, came from Sitka.

Early day seining was done with a big rowboat. After 1915, gas-powered boats became common. Cannery-owned traps were also used, and later became a key issue in the vote for statehood.

Commercial trolling began in Southeastern Alaska in 1905 with rowboats. By the 1920s motorized trollers were common, but most of them were still under 30. Troll caught fish in these years were “mild-cured” – lightly salted and chilled, and shipped south under refrigeration for smoking as lox.

SALMON

The first Salmon cannery in Alaska opened in Klawock on Prince of Wales Island in 1878. That same year one was built at Old Sitka, but it soon closed. Seining and later traps supplied the fish for canning.

Sitka didn't have another fish plant until 1913 when Booth Fisheries cold storage opened. It became Sitka Cold Storage in 1930. Today the old Sheffield Hotel stands on the site. Pyramid Packing cannery opened a few years later in 1918. It is still standing as the Murray Pacific building. Canneries in Peril Strait and at Sitkoh Bay (Chatham Cannery) also employed Sitkans.

The struggle for Native citizenship and land claims began when people had their traditional fishing stream rights taken by canneries. Prominent leaders and the founders of the Alaska Native Brotherhood, which fought for Native rights, came from Sitka.

Early day seining was done with a big rowboat. After 1915, gas-powered boats became common. Cannery-owned traps were also used, and later became a key issue in the vote for statehood.

Commercial trolling began in Southeastern Alaska in 1905 with rowboats. By the 1920s motorized trollers were common, but most of them were still under 30. Troll caught fish in these years were “mild-cured” – lightly salted and chilled, and shipped south under refrigeration for smoking as lox.

HALIBUT

Originally, halibut fishermen set out in dories. They set their ground line with buoys and anchors at each end, and pulled it up with the fish.

Most early West Coast halibut schooners were from Puget

Sound, but the first in Alaska were East Coast boats, which arrived in 1888. Some of the old-style boats are still in use. They are typically 70 to 80 feet long, with a high bow, two masts, and the house aft. Among the classic halibut schooners in Sitka at Eliason Harbor are the Republic and the Pacific.

Modern Sitka longliners are sturdy boats mostly glass or steel, with a bait shelter on the stern and hydraulic power block for hauling in the longline.

Halibut fishing changed in Sitka with the introduction of the IFQ (Individual Fishing Quota) system in 1994. Entry to the fishery was limited to those who fished in 1980s, but quota could be bought and sold. IFQs were seen as a solution to the problem of crowded open access fishery and loss of gear and lives.

Originally, halibut fishermen set out in dories. They set their ground line with buoys and anchors at each end, and pulled it up with the fish.

Most early West Coast halibut schooners were from Puget

Sound, but the first in Alaska were East Coast boats, which arrived in 1888. Some of the old-style boats are still in use. They are typically 70 to 80 feet long, with a high bow, two masts, and the house aft. Among the classic halibut schooners in Sitka at Eliason Harbor are the Republic and the Pacific.

Modern Sitka longliners are sturdy boats mostly glass or steel, with a bait shelter on the stern and hydraulic power block for hauling in the longline.

Halibut fishing changed in Sitka with the introduction of the IFQ (Individual Fishing Quota) system in 1994. Entry to the fishery was limited to those who fished in 1980s, but quota could be bought and sold. IFQs were seen as a solution to the problem of crowded open access fishery and loss of gear and lives.

World War II in Sitka

A crew ties up a sinking PBY (Sitka Historical Society)

Sitka had the only functioning Naval Air Station in Alaska at the start of World War II, but other stations were quickly built in Kodiak and Dutch Harbor. The original purpose of the Station was to service PBY Catalina seaplanes.

During the war, the Army and Navy launched hundreds of boats in Sitka ranging from patrol boats to barges and tugs needed for construction. The Army had as many as 26 shipwrights working on boat repair in Sitka during this time. All of them were stationed at the Japonski Island Boathouse, where up to 10 shipwrights could be found working in a 40-foot by 15-foot shop. Because of the space confines of the Boathouse, a great deal of work had to be done on the grid or at a work float.

During the war, the Army and Navy launched hundreds of boats in Sitka ranging from patrol boats to barges and tugs needed for construction. The Army had as many as 26 shipwrights working on boat repair in Sitka during this time. All of them were stationed at the Japonski Island Boathouse, where up to 10 shipwrights could be found working in a 40-foot by 15-foot shop. Because of the space confines of the Boathouse, a great deal of work had to be done on the grid or at a work float.