In the spring of the year I was in 3rd grade (1923), Dad exploded over something and quit his job at the Experimental Farm. He'd been dissatisfied and really never liked the job so I suppose it wasn't much of an issue only the trigger.

He quickly outfitted poor Cynthia and went back to fishing as he'd wanted to do all along.

Before the summer was over he was approached by a group of three townsmen to take on a job much more to his liking. The boomtime of the twenties had spurred many new industries, including fox farming. These men - Len Peterson, Felix Beauchamp, and a Mr. Ulrich - had invested in one of the first in the Sitka area. They leased 3 islands from the Navy (part of the outer defense perimeter) and bought a few blue foxes for breeding stock. These ran free on the islands and would not swim away as long as they were well fed. Roaming freely in a natural environment, they developed superior fur that brought top prices at the London fur auctions.

Len's bachelor brother, Carl Peterson, was caretaker on Legma Island. Another was needed for Maid and Tava Islands which faced each other and formed a somewhat sheltered harbor. The partners had a two-room log hut constructed on Maid Island, installed a 90 gallon kettle under a shed roof where the food could be prepared for feeding the foxes, and now asked Daddy to take the job.

Somehow, I doubt Mother had much voice in the decision. At least I do know that by the time my classmates were starting to fourth grade, we were learning to row a boat, split wood and dig clams.

More and more I helped with cooking and other housework, accepting my share of outdoor chores as we all did. At first it was exciting. Winter storms kept us indoors when we didn't have to carry buckets of food to the fox feeding stations. I was nine years old.

Mother procured discarded books from the Sitka Schools and tried to teach us, but just about every day she'd be called outside to help Daddy do something we weren't quite big enough to do.

Once again our lights were kerosene lamps or lanterns. Finally we progressed to gasoline mantle lanterns and lamps. A trough from the roof drained rainwater into barrels behind the house. When a big storm brought sheets of spray across the harbor drenching the roof to run off into the rain barrels the water was most unpalatable.

A wood stove served for cooking. To provide extra heat, Daddy contrived with a large metal drum, cutting a hole for the stove pipe and ventilation at the bottom and a door to feed in the wood at the top. Cutting wood was one of the biggest chores. Many logs drifted in on big storms, but not nearly enough.

Daddy would take us off to Chickenfoot or one of the other inlets over on Baranof Island where he'd spotted suitable trees. These he'd cut down, then with all of us pulling on the block and tackle, he'd haul them to the beach and into the water to tow home.

Once the logs were in the harbor at home we waited for the highest tides to float them ashore, then with block and tackle, hauled them into the best position for cutting. At first this was done by hand with a "cross-cut saw'' Dad on one end, Mother on the other. Later the partners furnished a second-hand gasoline powered saw--an awkward heavy thing.

It was V-shaped, about five or six feet long. The motor was on the apex of the V with the saw suspended on the right side to move from one cut to the next. Daddy would lift the lower, heavy motor end of the saw while someone else standing on the log would lift the upper end to the next cut. To do this, he would grasp the handles or upper edge of the V, slip the rope connecting the arms of the V over his shoulders and carefully edge the frame along to the next designated spot. Sometimes a cut would have to be a bit longer or shorter because a rock supporting the log would protrude and interfere with the saw.

Someone (first Mother, later Ruth or me) would stand on the log being cut to position the saw while Daddy lifted the motor end each time. I think these were called "donkey" engines although I'm not sure. At any rate, it was back breaking work for a ten-year-old (or any woman). We all learned to split the rounds and carry them to the shelter of the woodshed to dry for winter fuel. (My backaches started at a young age--the other children were even younger). The electric saws now-a-days would have been so much easier to handle, lighter and faster. I suppose someone has developed a battery powered one by now.

Even the youngest member of the family had to carry the smaller chunks of wood to the woodshed and there was no shirking. We knew our warmth and cooking depended on that wood. Since it was in the cold, stormy fall that we did the wood gathering, so as not to interfere with salmon fishing or school it was doubly brought home to us. I usually was the one to help move the saw because Ruth could split the blocks better. Between each cut I'd carry a load up the beach to the woodshed while Daddy tended the motor, ready to shut it off at the end of the cut.

The first year on the island, Ruth and I learned to fish off the rocks for bass and other rock fish for that yawning 90-gallon kettle. We learned to row a boat and could go further from the harbor, finally mastering an outboard motor. That kettle took two standard barrels of fish every other day the year around. It became our job to fill it until Glen was old enough to help. Usually l did the actual cooking, keeping the wood fire going until the fish were cooked enough to fall off the bones, adding a 50 pound sack of rice and a 100 pound sack of rolled wheat the last hour, gradually reducing the heat so it wouldn't scorch. We used a shovel to stir the mass, a constant job after the grain was added. When it was done, we filled 5-gallon tinned milk pails and set them into a trough of cold water to cool.

Once the "mush" was cool enough we trudged off across our island in all directions carrying our buckets of food to previously arranged feeding stations. Daddy did a wonderful job of hacking out trails that led to the various fox dens. At first we dumped the food onto the ground. Later we used large dish pans. Slowly, Daddy built trap houses in each place but this took several years to complete. They were very simple, but effective of 1" X 12" spruce boards with a slanted tar paper covered shed roof. A simple door on strap hinges let us in and out.

The foxes ran up a cleated board to a high opening then down inside to the huge dish pans for the food. At trapping time we simply removed the inside ramp and they couldn't get out.

Getting around Tava Island, and later Legma, was a different matter. First, they were much larger and the shoreline more rugged. Maid Island was about a mile and a half in either direction. At first we children could only manage 2 full five gallon buckets. (Perhaps this is why my arms are so long.) Inspired by pictures, Daddy carved us wooden yokes so the real weight was on our shoulders. The younger ones, Glen and then Donald were-e allotted the closer stations and gradually Ruth and I were promoted to the "boat."

Until we could manage the outboard motor, we rowed around Tava (and later Legma when Daddy took it over). One would manage the outboard (usually Ruth) until we were abreast the feeding station, then cut the motor and row to the rocks where the other would balance on the bow of the boat, a bucket in each hand. Ruth would watch and ride the waves in on the "big one" while I would jump onto the chosen boulder--often skinning my knees if I slipped on the seaweed and barnacles. After a dash to empty the buckets in the trap house, I'd rush back and wait for Ruth to edge the boat back into shore where I'd leap in with the empty buckets as the wave lifted the bow. Familiarity with the job never robbed me of the fear that I'd miss when I jumped so I'd land in the heaving surf, a sure death. While I never did miss, it was a fuel for nightmares that persisted long after I'd left the island. Ruth was more agile and better coordinated. Her look of contempt when I'd land in a heap on the bottom of the boat soon taught me to keep my fears to myself. She managed the boat better and was stronger so it was natural she should do this part and I understood. Until Ruth and I were 10 and 11 Daddy, with Mother's help, would do the boat work.

To house us all that first year was a problem. Early winter storms were fierce with the surf booming against the rocks and the wind whipping the tops off the white caps blowing across the harbor to deposit great sheets of salt spray onto the roof (which leaked) and contaminating the water supply. At times the spray was so constant and thick that we couldn't see the shore of Tava.

That first Thanksgiving Day brought the highest tides of the year along with a fierce storm so water beat its way up the sandy beach and all over the floor by at least an inch. The chinking of moss between the log walls blew out and we were cold and wet despite the efforts of Daddy and Mother to keep a fire going in the very elderly stove. The breeze through the cracks even made the lantern hanging on a rafter swing so much that Daddy had to take in down and set it on the table otherwise it could have smashed and set fire to the house.

The storm lasted several days and Daddy worried constantly that Cynthia would drag anchor and land on the beach.

This was meant to be a very special day. The partners had sent a rare treat, pork chops. Mother cooked them, splashing about in at least an inch of icy tidewater. They smelled wonderful and tasted even better.

Following that storm was great activity. First Daddy and Mother consulted on a breakwater to keep other high tides from the cabin. With pry and peaveys they rolled great boulders into a wall about 10 feet from the cabin. All we children were set to carrying smaller stones to fill the space behind the wall, stones as big as we could carry until we had a ledge seven or eight feet higher than the beach. At first it was fun.

Great heaps of seaweed had been blown in on the storm and littered the beach. Daddy constructed a wheelbarrow from scraps of lumber and saplings. Using this and buckets, we trundled the seaweed and kelp to a spot designated for a garden. Left there, the constant rain could leach it of sea salt.

Meantime Daddy mended the roof as best he could. It was too stormy to go to Sitka with the Cynthia and until the weather was better we "made do". Gathering sphagnum moss was an all family occupation and Daddy "chinked" the cracks between the logs that formed the walls of the house so we were warmer. He also started cutting driftwood for the fires and stacking it under the lean-to he constructed of bits and pieces.

The big brass bed Mother and Daddy had brought from town fitted into one end of the bedroom, just barely. For us, Daddy constructed bunks on either side of the other end of the room using pieces of board and saplings for uprights. Chicken wire for the bottom over which Mother folded a quilt as mattress.

Donald and Carl had the smaller bunks on one side, Glen, Ruth, and I had the other side, three high with me on the top and Ruth in the middle. Empty wooden cartons that had held evaporated milk were the only chests for "foldables".

The other room had a decrepit wood cook stove, a "cabinet" with sugar and flour bins and two shelves above the counter top where the Seth Thomas wedding gift clock reposed flanked by cornstarch and other foodstuffs as well as the medical supplies (bandages, paregoric, iodine, tincture of mercury and Epsom salts). There was a rickety table and two or three straight chairs.

After a trip to town for supplies, Daddy built window seats with lockers beneath for clothing and other necessities. Those windows--two side by side with three six-inch panes, two high in each were the only daylight in the room. Mother soon had her precious geranium slips there on the log window sill. She made curtains from an old remnant that cheered the room considerably.

Between storms Daddy continued to go to town that winter. Because of the short days and violence of the weather he usually had to stay over so none of the rest of us went. Cynthia was too old and the motor too unpredictable. At best she could manage no more than five miles per hour. Storms brought heavy seas with giant rollers eight to ten feet or more high. There were no radios to give weather warnings then, either, so sometimes he'd have to be gone for several days.

Sears catalogues were indeed dream books and we'd spend hours drooling over them, not really expecting anything. Necessities were ordered, clothing, bedding, etc., only when there was money from selling fish.

At first the partners paid Daddy a salary (probably not much). Major food supplies were purchased at McGrath's or the Cold Storage store. This meant things like flour, sugar, yeast, potatoes, and rice. Meat was the venison Daddy shot, the fish we caught, the clams we dug. Shortening was the rendered venison fat (tallow) and Mother made our soap from it with lye from wood ashes. We lived a primitive frontier life.

When summer came and brought the fishing season, Daddy was off and we continued the fishing and feeding of foxes. Salmon brought in necessary cash.

Sometime that first winter Daddy had a brainstorm and Mother concurred so two programs were started. First, it was obvious that we children were not yet big enough to do a full man's work and second, that we did need to be educated. Daddy proceeded with a letter writing campaign. First, the Territorial School System informed him they would start a school and provide a teacher for no less than ten pupils. At that time Ruth, Glen, and I were of school age. Next, it would have to be situated where a teacher could get room and board.

The fox farm owners replaced bachelor Carl Peterson with Chris Jackson on Legma. Chris had fished and saved enough money to go back to Norway for his family. George was Glen's age and Johannah a year younger, both of school age. Of course they had not yet learned English, but that didn't matter. With their father's help and school primers even their mother soon knew the rudiments, and from the beginning we could communicate. We delighted to have other children only a mile away. For a school, that now meant five of us.

Daddy's letter writing brought other results. Since he really needed help from an adult, he persuaded his cousin, Foster Mills and his wife to come. They had two children, Jane and Russell. That meant two more for the school. After they arrived late that spring, Daddy and Foster built a house for them on the far side of Tava where there was a harbor. Jane and Russell could take the trail across the island and go with us, and we picked up George and Hannah on the way. Now we were seven for school.

Another result of Daddy's letter writing was the arrival of his Uncle Seth with this second wife, Edna. They, with the Houghs had decided to try their luck at fox farming. The Houghs had an adopted son, Donald, about 7 or 8 so we had another boy for school.

Ed Harris and his wife settled next on a nearby island with their two little girls, but only Eleanor was ready for first grade.

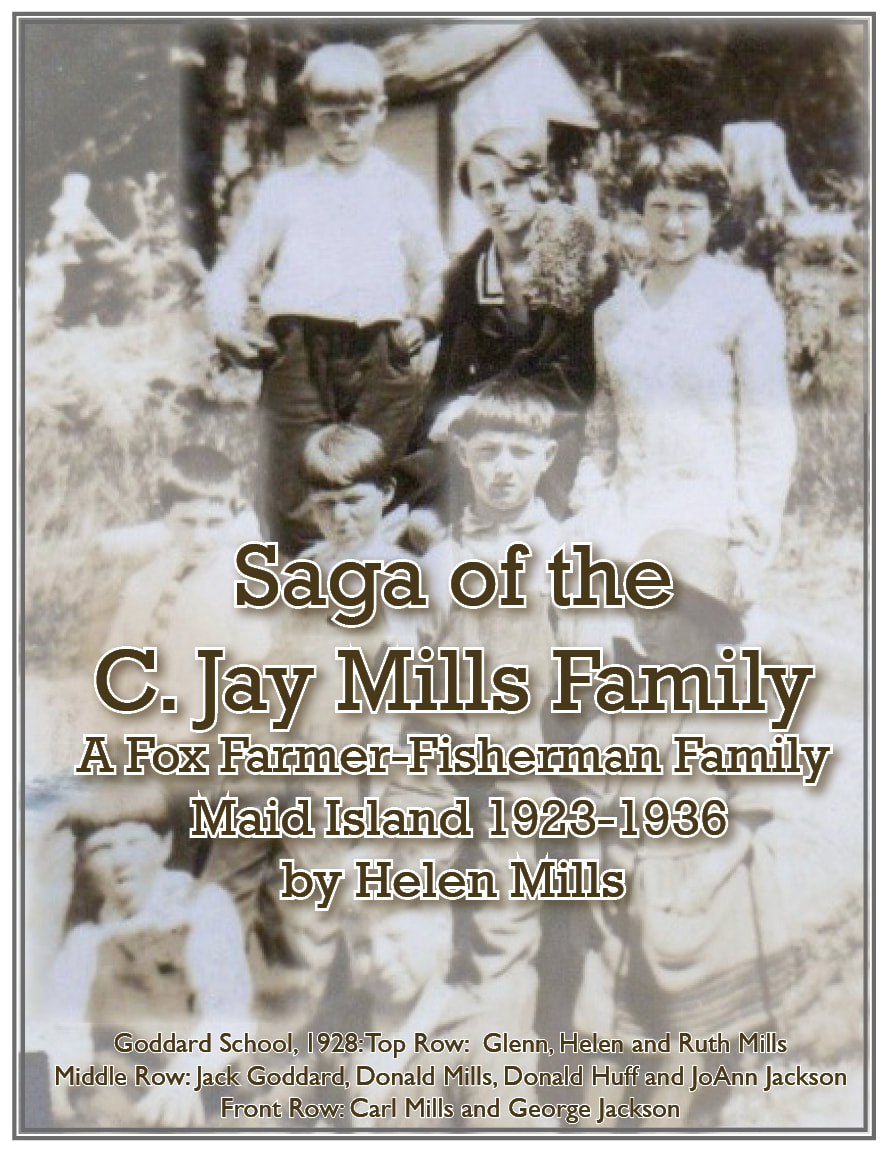

Another wave of letter writing and by the time we'd been on the island a year and a half a school was established at Goddard Hot Springs three long miles across open ocean. There was a resort hotel at Goddard where a teacher could live and a one room cottage they were willing to rent for a school. Because of the stormy weather in winter, the session was established April 15 to October 15.

During the winter following those first two years, the fathers volunteered their labor and a one room school house was built a mile down a trail from the hotel. The teacher trudged, storm or sun, each day. A Miss McCann was the first teacher there and she stayed several years. She was followed by a Mrs. Garretson, I think, although a Miss Whitmore possibly came between.

At first Mother or Daddy took us to school in the rowboat or with the outboard motor. In very rough weather, if he was home, Daddy took us on the Cynthia. If we ''sheared a pin" on the outboard or had other engine problems like spray getting in the carburetor, we'd end up rowing. It was heavy, scary going, at least for me. The boat itself was a 17-foot flat bottomed affair with two sets of oars. Because of the numerous rocks and heavy kelp beds, boats with keels were useless for getting near the shore, either for feeding foxes or as a school boat picking up children. Moreover, the wider, flatter boats were safer and less likely to tip over, even though cumbersome.

I've never known why exactly Foster and Louise decided to leave, but they moved to Sitka where Louise worked at the Pioneer Home and Foster became custodian at the Post Office.

The Houghs and Seth Mills family next departed for the "Outside" (Alaska was still a territory). Harrises moved to Sitka because they couldn't stand the isolation and he ran a hardware store in the (Indian) Village near the cannery.

But I'm ahead of myself. One summer there was great excitement. Barrette Willoughby wrote a novel with a fox farm island near Kodiak as background. I can't remember the story at all, but instead of filming it in the stormy Kodiak area, Goddard Hot Spring was selected. All the actors and work crew were boarded there at the hotel. The scenery around the islands and ocean were easier to photograph because there was more good weather. I do know that Ed Harris and his boat, Spark Plug, were used in the filming, much to my father's disgust. Instead of a fox, a dog was disguised and used. In order to fit the plot, the background film was run backwards. These were liberties my father would not tolerate. He would not permit us to see the film when it was shown in Sitka, citing those faults, yet I think he must have seen it on one of his trips to know so much about it. For us, movies always were "no, no," and NO!" even when we were in town.

All my life I've heard: "Time and tide wait for no man." Our lives were governed by this creed along with the weather and the changing seasons, the long summer days when it never was really dark at night to the short winter days when daylight came at about 9:00 AM and was gone by 4:00 in the afternoon. A tide table was more important than a calendar. On "minus" tides we could go for abalone if the weather was calm enough, reaching deep down to pry them from the rocks where they hid unaffected by the surf that boomed during bad storms. The bigger clams could be dug then right on our own beach. Feeding the foxes by boat we tried to go near time for nigh tide because we could get closer to the stations with the boat and there was less chance of hitting submerged rocks. Logs for firewood were towed ashore on the highest tides so they were floated as far up the beach as possible.

All activities were planned according to the tide table, especially meals and even the youngest could quote the high and low times.

It was a cardinal rule that we all eat together. If work delayed some of us (say we were out feeding foxes) the meal was delayed for all.

Mother and Daddy agreed that we be taught manners fitting us for any society when we were grown. The table was properly set for each meal including cloth napkins. Breakfast and lunch the oilskin cloth sufficed, but for dinner a proper tablecloth was used. Dad carved if he was home and there was roast or fowl. Food was passed and we had to have some of everything served. If we fussed about anything Dad would reach over and give us a double helping. We couldn't leave the table until it was finished. Many times since I've been grown I've been grateful for that edict because it taught me to accept strange foods anywhere in the world even though the very sight was disgusting.

We learned to use the correct silver even though it required polishing, not to talk with our mouths full, how to cut food, never, but never to lean elbows on the table and shovel food in. If we persisted in sticking our elbows out too much Dad shoved a book under and we had to keep it there. Disagreeable topics were eliminated at the table and we had to converse around the table on acceptable subjects. Mother usually read a short selection from the Bible at breakfast and we took turns saying grace at all meals.

Next: Life on the fox farm: groceries, hunting, fishing, gardening and entertainment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed